- SOM

- Departments and Offices

- SOM Departments

- Pediatrics

- Pediatric Update

- 2023

- Fall

- News Articles

News Articles

Unprecedented UMMC Kidney Swap: A Lifesaving Exchange of Donors Gives Two Patients a Second Chance at Life

Jeff Hughes of Hattiesburg and Dakota White of Mize, both in need of life-saving kidney transplants, faced a challenge when initially identified donors were found to be incompatible. Fortunately, a unique solution emerged: the family members who initially volunteered to donate, though incompatible with their intended recipients, turned out to be perfect matches for the opposite patients.

This internal kidney transplant swap was a historic first for the University of Mississippi Medical Center and provided new hope for both Hughes and White.

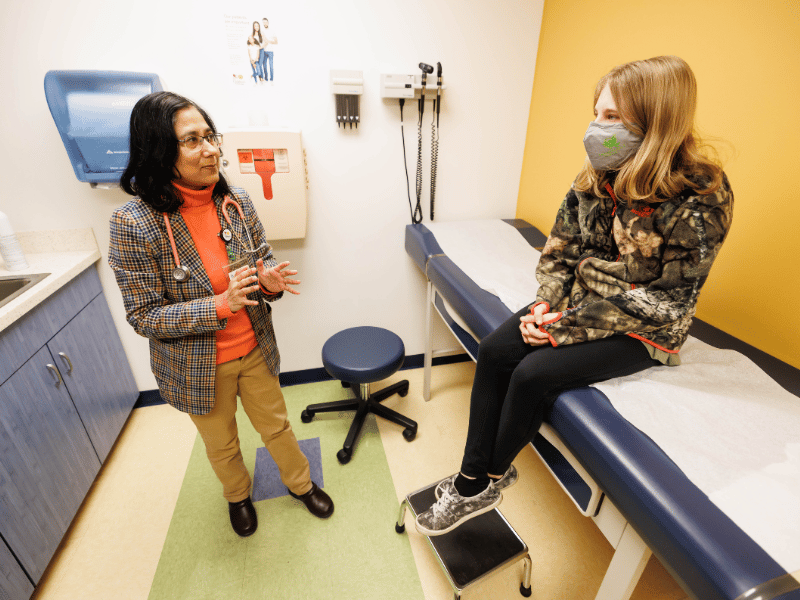

Shortly after Dr. Sabahat Afshan, a pediatric nephrologist, joined UMMC she began taking care of 16-year-old White.

“Since 2015, I’ve been her nephrologist—keeping her stable, monitoring her labs, and slowing down the progression of her chronic kidney disease," she said, adding White was doing well and in compliance with check-ups and medication.

Although Afshan had previously recommended White for a kidney transplant, an evaluation revealed that she needed the COVID-19 vaccine before surgery. While awaiting the second vaccine dose, White unexpectedly progressed toward kidney failure, prompting dialysis initiation while Afshan continued the evaluation.

“Her mom wanted to donate a kidney, but we found that she wasn’t a perfect match,” said Afshan. “We were talking about options; her mom really wanted her to have a living donor donation. It wasn’t long after that, we heard about the possibility of an internal candidate swap. The internal swap was great news because it’s easier than having an external swap because those could take hours to have the kidney.”

In this remarkable turn of events, White spent less than 24 hours on the recipient list before her mom, Amanda Creel, received a call confirming they had found a suitable match.

“I think it’s important to realize the complexity of pulling something like this off,” Dr. Mark Earl, chief of transplant surgery, said. “A lot of times we have people who want to donate, but the kidneys don’t match. Most times that is due to blood type compatibility, but also human leukocyte antigens—basically antibodies to other people—that make that difficult.”

Hughes had also been dealing with kidney failure for several years, but after contracting COVID-19 in 2022, his situation escalated.

“My GFR went down to five, my creatinine went up to about twelve, but I was still really healthy,” Hughes said. “So I got a PD catheter installed, but I never went on dialysis.”

He knew things could be getting worse when he became increasingly lethargic. Hughes booked an appointment with his primary care physician, in search of a solution.

“I told him I was feeling completely drained,” Hughes said. “I was white as a ghost. The doctor told me to drive to the hospital immediately. But I went home to pick up my wife.

When Tina and I got to the hospital, I told them about my hemoglobin level (protein in in red blood cells that carry oxygen) and everyone started rushing around, shouting; apparently it was very serious. They did a transfusion, which gave me some antibodies that made my donor match a little more complex.”

Hughes was put on the donor list at UMMC and his sister-in-law, Kathy Rayborn, immediately volunteered to donate to him. She underwent evaluation but was determined an incompatible match. Hughes was soon going to be added to the national transplant registry, but a miracle happened just in time.

"Low and behold, someone right here in Mize, Mississippi matched me and Kathy matched her daughter,” Hughes said. “It happened so fast.”

Rayborn, who was disheartened by being unable to help her brother-in-law, expressed gratitude for the opportunity to give a life-saving gift and emphasized the joy of helping others in need.

“It meant a lot to us that we were helping such a young girl,” Rayborn said. “Of course, I would do anything for Jeff; but when you get the opportunity to help other people, it’s truly a blessing.”

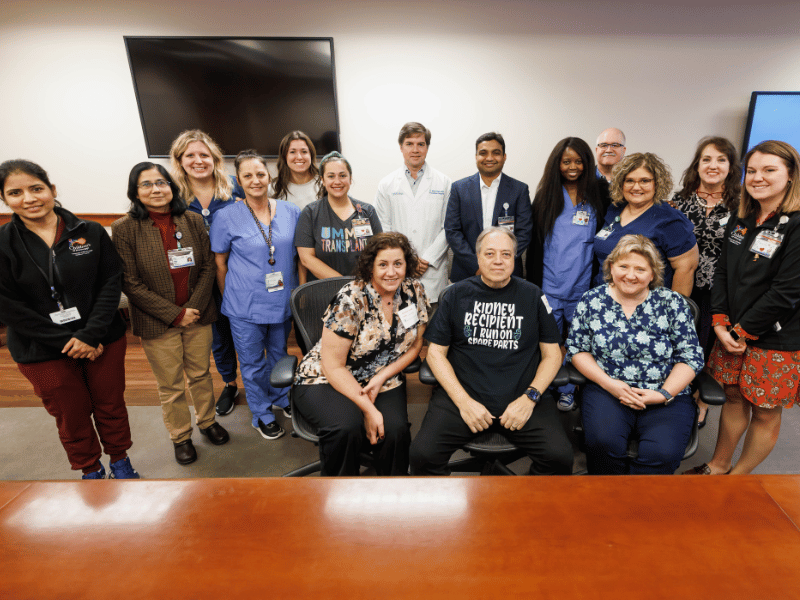

The UMMC transplant team worked together in making complex procedures like this a reality. Beyond the spotlight of the surgical room, their meticulous efforts spanned various departments, from the immunopathology lab to the nurse coordinators and nephrologists. The team's commitment extended well beyond the surgery day, with months of intensive preparation and checks to ensure every detail was perfect.

“We can’t just sit down with a chart and draw lines from one person to another,” said Earl. “The surgery gets all the attention, but that’s probably actually the easiest part. People don’t realize all the work that goes into pulling something like this off.”

“You want to make sure the donor is in pristine shape, absolutely nothing can go wrong with them,” Dr. Pradeep Vaitla, nephrologist and medical director of kidney transplant, said. “The added complexity of having unrelated donors and recipients and making sure everyone is in perfect shape for that day is a lot. If even one thing is off, it costs everything. A lot goes beyond the day of surgery. There’s at least three to six months that goes into it to make that day happen.”

Rayborn recounts that she had no concerns on the day of surgery, grateful for the extensive quality care she received.

“The energy in pre-op that day was so beautiful,” Rayborn said. “I knew I was going to be taken care of. As someone who has been operated on before, it’s not always like that. It makes me wish there was that kind of excitement and warmth in every pre-surgery.”

Creel shared that her daughter was nervous for everyone on the morning of surgery but agreed that there was positive energy flowing through the air that day.

“I remember being wheeled into surgery, seeing Kathy getting into her bed, and wishing her good luck,” Creel said.

“Obviously all surgeries are a big deal,” said Earl. “They all require attention to detail, not just in the technical aspect of doing the operation, but also ensuring the patient is prepared and ensuring that the operation is going to be as safe as possible.

For a living donor, my awareness and intensity go up to another level. This is someone who doesn’t need surgery. There’s no medical benefit to them. This is someone who is risking their life to save another. So that, to me, always adds a whole new level of double, triple, quadruple checks to make sure everything is going to be perfect.”

Even after the procedure, Creel said the transplant team has been very thoughtful with following up on the patients. She notes that Nikki Little, living donor coordinator; Ashley Hilsabeck, pediatric coordinator; and Dr. Christopher Anderson, James D. Hardy professor and chair of the Department of Surgery, have all made them feel comfortable throughout the process.

“Nikki has called several times to check on us, and Ashley is at every appointment Dakota has,” Creel said. “She also came to check on Dakota while she was in the hospital after her surgery.”

White and Hughes are recovering smoothly post-surgery, feeling better than they had before.

“Dakota is doing great now,” Afshan said. “I just saw her. She’s definitely a different kid, more energetic and living her life. For the past several years, I’ve been telling her to restrain fluids, and now I’m telling her to drink more fluids. I was telling her not to eat all these things, and now I’m telling her to eat more of them.”

Afshan said that the nephrologists will continue to monitor the patients closely on their road to recovery, seeing them twice a week for the first several months and then spacing appointments farther apart as their kidney function improves.

Hughes now wishes to spread the word about the reality of giving as a living donor and the impact that it can have on a recipient.

“I think that it’s important that the public understand that a healthy person can donate and live a long life with only one kidney. And it means so much to the person who, quite frankly, doesn’t have that future ahead of them. And when you get that kidney, your life is so different. It is honestly night and day. We just want to encourage anyone thinking about donating. It is miraculous for recipients.”

Rayborn agreed that “it’s miraculous for donors as well, knowing that now you both can live a healthy life.”